If you’ve been a regular reader, you know that in the last week of December I went on a Himalayan trek. Let me tell you more, and introduce you to the Pain-Pleasure Index.

When I shared my plans to go on the trek with my family and close friends, a common comeback was ‘Who signs up for a vacation that involves so much pain?’

Judging by the way the trekking industry is growing in India, a lot of people. And on reflection, I’m exactly the kind of person who does so.

Let me explain. For 15 years while I was playing cricket, many of those as a professional, I bartered pain for pleasure every day. Fast bowling is the most demanding activity within the game of cricket physically, and training for it involves a significant amount of pain. Every training session is designed to punish the body. Every net session where we run in and bowl for an hour pushes that punished body further. Then there are injuries, which very often mean that a fast bowler is playing through some pain or the other.

For the most part, it’s not fun. But I did it anyway for a decade and a half. For two reasons:

I love the sport and I accepted that that involved some physical pain.

For the intense highs of winning a battle with a batter, or winning a match for my team. Relatedly, to avoid the intense lows that come with losing.

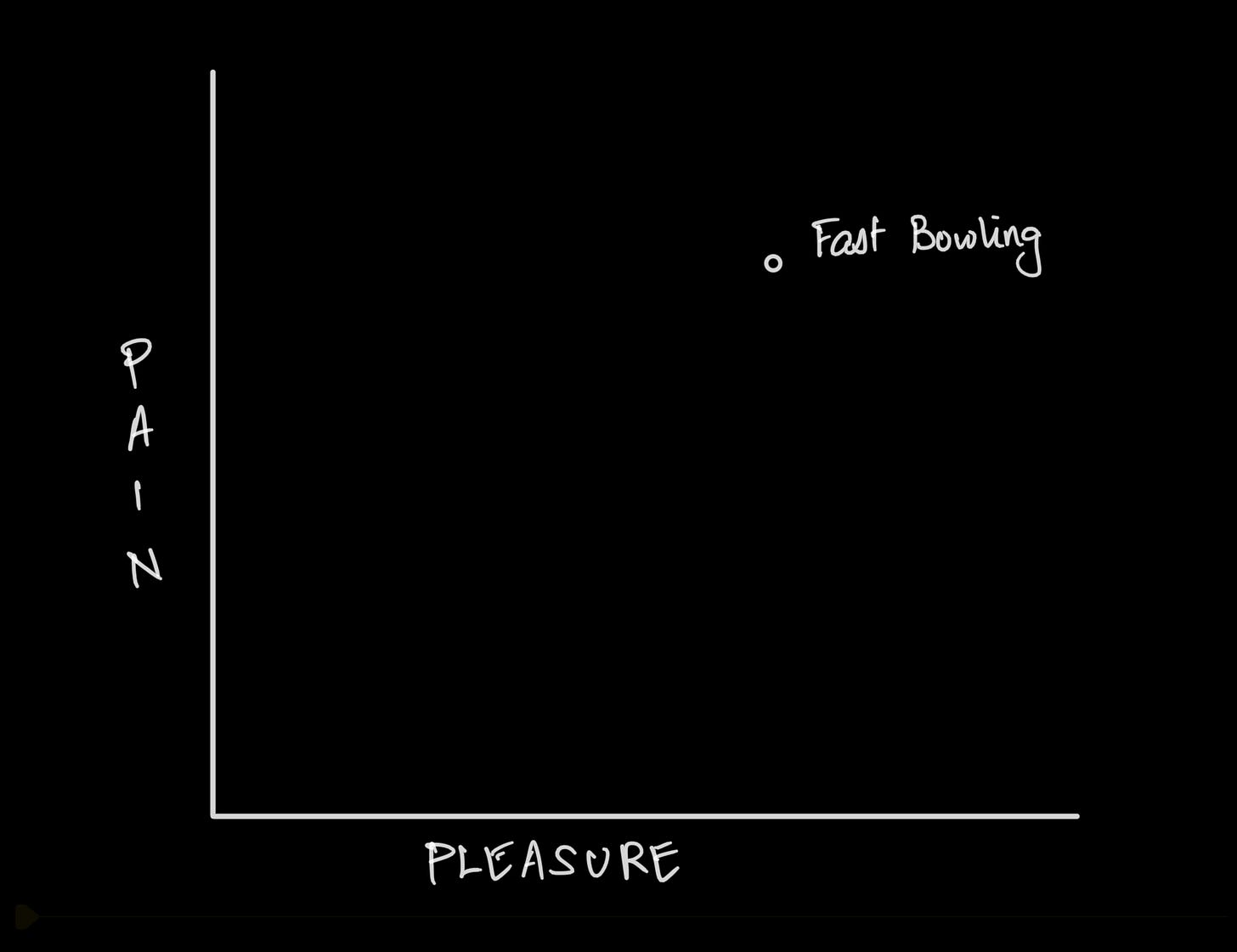

I never articulated all this while I was playing, I just did it. But the recent trek give me the chance to articulate this on what I call the Pain-Pleasure Index. It looks something like this.

Fast bowling is a high pain, high pleasure activity. And so since I retired, I also took a break from intense physical activity. I’m fairly regular with some form of light exercise, but I’m nowhere close to the fitness levels I had while I was playing, and have no desire to get there because I’m too familiar with all the pain I know will be involved.

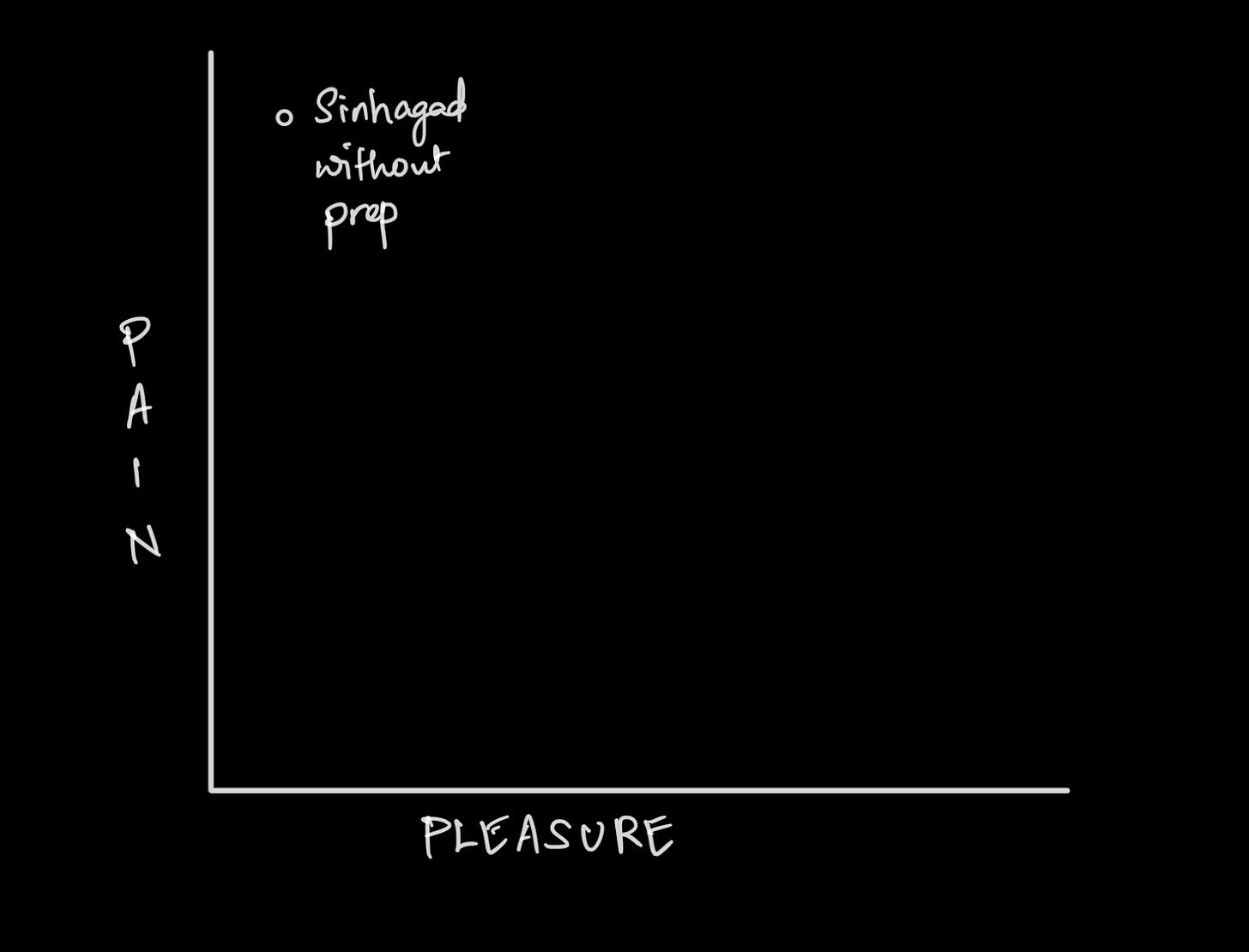

I first started thinking about this Pain-Pleasure trade off when I went on a hike to Sinhagad, a fort outside Pune, last monsoon. Like I said, I’d been doing very little physical activity in the past few years, and this hike came on the back of a spell where I’d done no workouts. But I wanted to experience Sinhagad in the monsoons, trek through the clouds, look over the mist-filled valleys. So I went anyway.

Needless to say, it was painful. My out of touch cardiovascular system rebelled, and I huffed and puffed to the summit in 1:20 hours. I usually take an hour. At various points on the climb, I asked myself, ‘why am I doing this’. The views were great and I got some nice photos, but I was in no condition to enjoy the experience.

So when my best friend floated the idea of a winter trek in December, my first instinct was no. I’m not a fan of extreme temperatures, and trekking in sub-zero through snow sounded like too much pain and who knows how much pleasure.

But the more she told me about it, the more I became interested. For three main reasons:

The trek had a fitness requirement, to run 5 KM in under 40 mins. This appealed to me. Sinhagad had shown me what a slob I was becoming, and I knew I had to get back on the proverbial treadmill. The prospect of having a fitness target in front of me appealed to my competitive instincts, and gave me the motivation to start jogging again.

I was looking forward to the people I would trek with, rather than the place I would trek. We were travelling with a group who I’d been introduced to through my friend, and who I’d enjoyed spending time with.

I had been working to find more balance between work and life in the last year, and signing up for a trek with friends sounded like a good way to build some non-work related travel into my year.

Plus, I had never experienced snow. And so I signed up to summit Mount Kedarkantha, and reached the top, 12,500 feet high, on the 29th of Dec. Where did it rank on the Pain-Pleasure Index?

The trek itself was not without pain. The climbing was fine, my cardio preparation served me well, and I was never out of breath on the slopes. The pain came from the cold, which seemed to seep through my shoes and turn my toes uncomfortably numb. On the summit climb, my fingers went that route as well.

Will I do it again? No, not in winter.

But the pleasure of the overall trip outweighs those painful experiences. The lovely weather we were permitted made for some great photographs and even better views. And the people were great, not just the group of friends I went with, but also the organisers of the trek, India Hikes. Their efforts to leave the mountains better than we found them really resonated with me, and the non-crowded route they took to the summit really allowed us to disconnect externally and so build stronger internal connections.

Am I glad I did it? Hell yes.

I’ve been meaning to write this post on the Pain-Pleasure Index for a while, and the trek gave me the perfect opportunity. It’s also re-emphasised the importance of physical activity, and overall physical and mental health in my life, which has become a part of my routine again, a shift in lifestyle. Perhaps what I’m most proud of is turning down a work commitment that came up around the same dates, and so the trek was emblematic of the balance I have been striving to build into my life.

Do you have any frameworks that you use to think about decisions in life, like the Pain-Pleasure Index? I want to hear about them. Comment below.

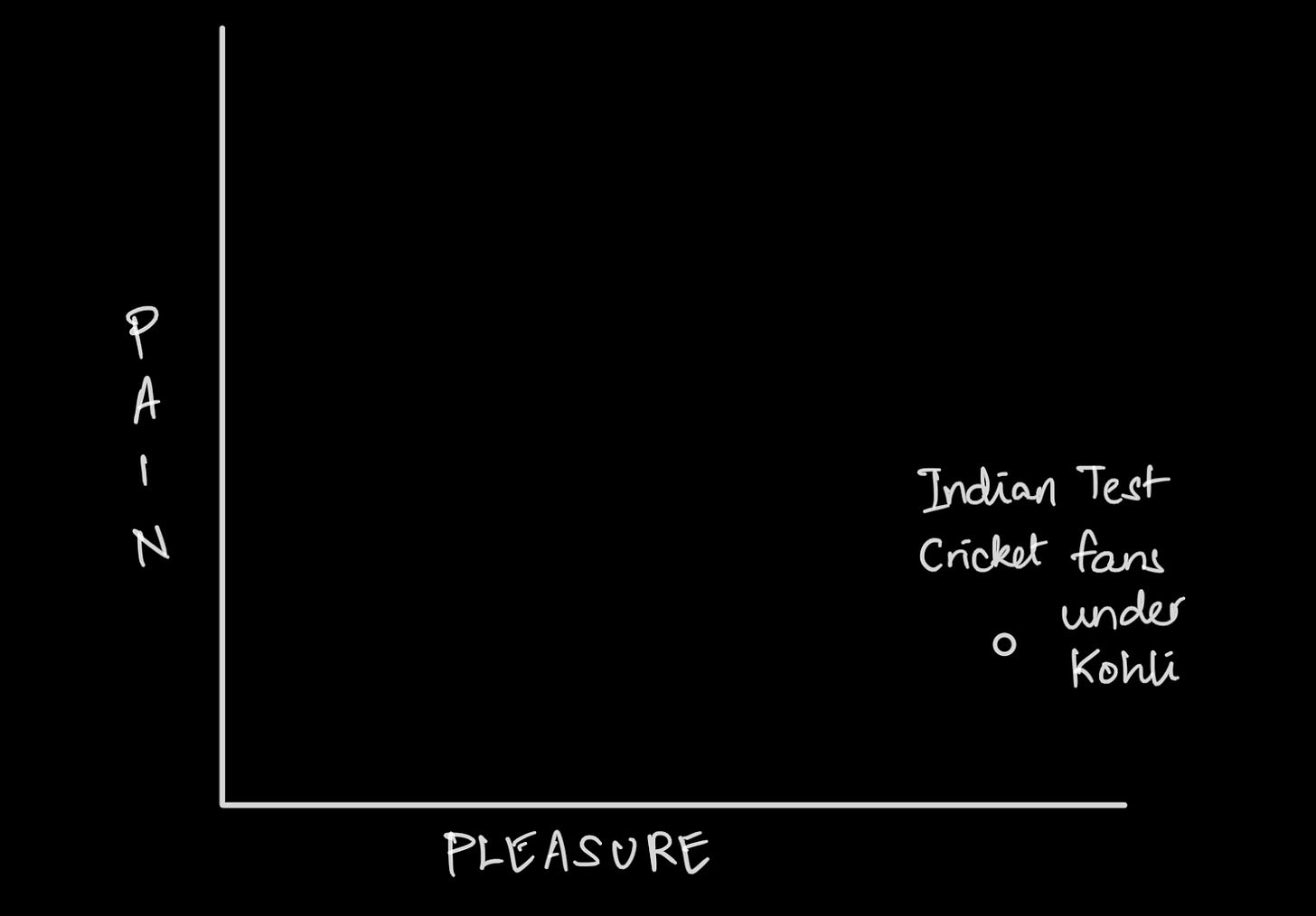

On Kohli:

I’m thinking about Virat Kohli’s decision to quit captaincy in the same context. It seems, from the outside, that captaincy in the current environment is a huge drain on Kohli, one he no longer thinks is worth it. Even though his position as Test captain was not under threat or question, there is no Ravi Shastri in the dressing room, no CoA in the BCCI, who are backing him to the hilt. Kohli obviously derives a great deal of pleasure from winning games for India, and leading the Indian team to wins, but the pain that must be associated with it seems to have gotten to levels that override that pleasure.

Which is a shame. The timing of the retirement has reemphasised the value of Kohli the captain, in that there is no clear replacement. Rohit Sharma is the obvious tactical successor, but is he fit enough physically to lead in all three formats, and is he a long term option? KL Rahul is the other contender, but he has only just cemented his spot in the side, and making him Test captain might require resting him from some white ball games. Rishabh Pant is the one player who is likely to play every Test from a fitness and form point of view, and don’t be surprised if the selectors go that route. And don’t discount Jasprit Bumrah. India can consider a bowling captain, for he has enough tactical support in the XI to not have to think about field placements while bowling.

But to Kohli, we owe our gratitude, for playing a big part in India’s loss in South Africa being the exception, not the norm. He’s made the Pain-Pleasure index of the Indian Test cricket fan quite the picture.